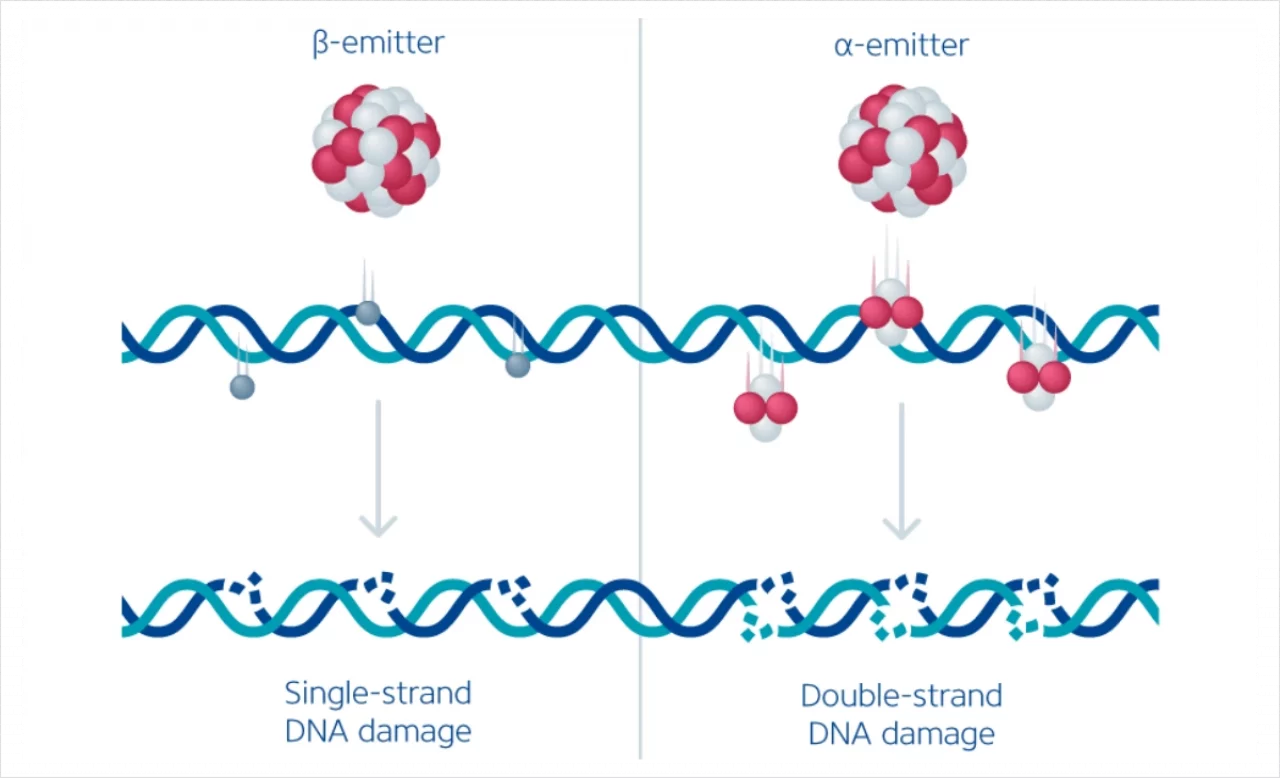

Therapeutic radiopharmaceuticals are labeled with either beta- or alpha-emitting isotopes. The tissue penetration of these isotopes is inversely proportional to their linear energy transfer (LET). Beta-emitting radioisotopes, e.g., Yttrium-90 (90Y) and Lutetium-177 (177Lu), have a low LET and an indirect cytocidal effect on tumor cells, primarily by ionizing reactive oxygen species that cause mostly single-strand DNA damage. The tissue penetration of a few millimeters allows for targeting cells and cell clusters with a low expression of the targeted surface molecule while mostly sparing healthy surrounding tissue.

Find out the difference between c.a. and n.c.a. Lutetium-177 production in our freely available infographic in the library section.

On the other hand, alpha-emitting radioisotopes (e.g., Radium-223 & Actinium-225) have a high LET across a short distance (a few cell diameters). As such, they deposit tremendous energy and cause irreversible damage to target cells. Due to their low tissue penetration, they cause even less collateral damage to surrounding tissue. However, they may not be able to target cell clusters in the tumor that do not express sufficient amounts of the target molecule. (Hatcher-Lamarre JL et al. 2021; Mango L et al. 2017) (Figure 1).

The radiopharmaceutical substance is dosed significantly higher for therapeutic purposes than for imaging. β-emitters are administered at several GBqs per dose, while for α-emitters, doses in the MBq range are used. Unlike external beam radiation, where a homogenous radiation dose is delivered to the tumor area, TRT delivers a heterogenous radiation dose within tumors at a steady but low absorbed rate (Kerr CP et al. 2022).

Learn more about targeted radiopharmaceutical therapy and the mechanism of action of radiotherapeutic agents by downloading the infographic from the library.

Dosimetry in Radiopharmaceutical Therapy

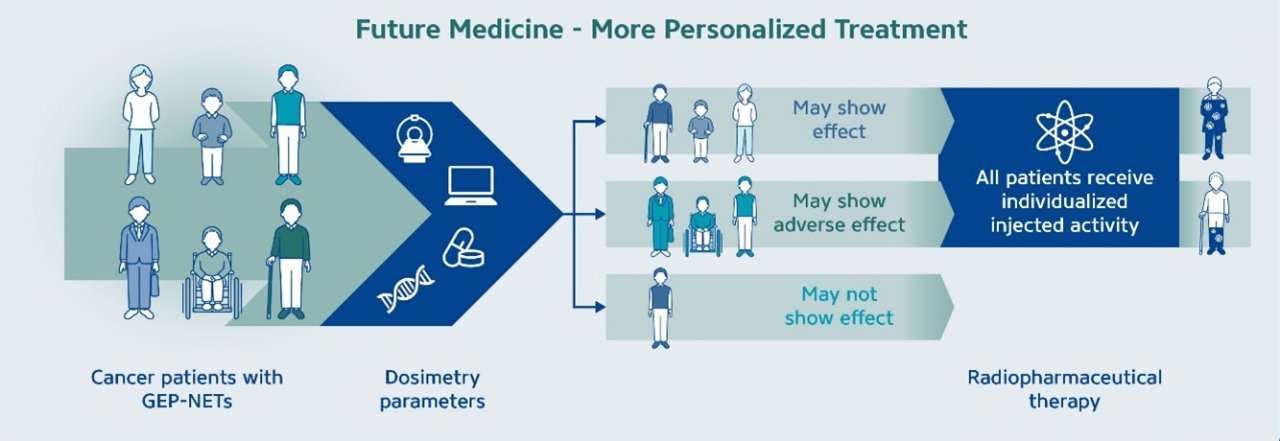

The goal of dosimetry is to estimate the absorbed dose delivered to critical organs and tumors, which differs from the injected activity of the radiopharmaceuticals (as further illustrated in Fig 1 below). Interest in internal dosimetry is increasing as a way to personalize and optimize radiopharmaceutical therapy (RPT), as some studies have demonstrated a dosimetry-based approach can result in positive clinical outcomes can be achieved by using individualized absorbed dose estimates rather than a uniform fixed dose to all patients (O’Donoghue, J. et al. 2022). This concept is schematically represented in the graphic below, which illustrates how dosimetry parameters can lead to individualized injected activity (Figure 1). In addition to optimizing the injected activity, this personalized approach can also assist in helping to opitimize the number of treatment cycles for each patient.

Current challenges and emerging opportunities of clinical dosimetry

However, dosimetry is seldom implemented in clinical practice and has generally been confined to early-phase trials and considered for only a small subset of patients (Bardiès, M. et al. 2024). Several significant barriers hinder the adoption and practice of clinical dosimetry,which may include:

Absence of controlled clinical trial data demonstrating that dosimetry improves the safety and efficacy of RPT

Lack of reimbursement for additional costs related to dosimetric calculations and imaging

Limited number and expertise of medical physicists to perform dosimetry routinely

Need for specialized infrastructure

Despite these challenges, work is underway to enhance the accuracy and reproducibility of patient-specific dosimetry by integrating artificial intelligence tools, enabling greater automation, standardization, and consistency. Furthermore, the nuclear medicine community, such as the EANM, has published comprehensive guidelines to customize dosimetry protocols for routine clinical practice, considering the resources available in different settings (Gear, J. et al. 2023). The Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH) Biomarkers Consortium’s Precision Dosimetry Imaging Biomarker (PDIB) Project is contributing with dosimetry data to help establish standardized imaging and dosing methods.

Although multi-time point dosimetry is considered the gold standard for estimating organ and tumor doses, several studies also focus on single time point (STP) dosimetry, which could decrease the workload for clinical medical physicists (Chicheportiche, A. et al. 2023 and Spink, S. et al. 2024). STP dosimetry uses population data on pharmacokinetics and may be prone to error in patients with reduced kidney function (Vergnaud, L. et al. 2024). This approach demands careful assessment prior to implementation, and it is essential to conduct further clinical trials, including head-to-head comparisons with the multi-time-point dosimetry, to confirm the validity of these simpler methods.

To learn more about the basics of dosimetry and the steps involved in a clinical dosimetry workflow, please check out the webcast series of Prof. Manuel Bardiès in the library section. Click here.

References:

Hatcher-Lamarre, Jasmine L. et al. 2021. “Alpha emitting nuclides for targeted therapy.” Nuclear Medicine and Biology, 92, 228–240. DOI: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2020.08.004

Mango, L. 2017. “Theranostics: A Unique Concept to Nuclear Medicine.” Archives of Cancer Science and Therapy 1(1): 001–004.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.acst.1001001Kerr, Caroline P. et al. 2023. “Developments in Combining Targeted Radionuclide Therapies and Immunotherapies for Cancer Treatment.” Pharmaceutics 15(1): 128. DOI: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15010128

O’Donoghue, J. et al. 2022. “Dosimetry in Radiopharmaceutical Therapy.” Journal of Nuclear Medicine 63(10): 1467–1474. DOI: 10.2967/jnumed.121.263740

Bardiès, M. et al. 2024. “The Translation of Dosimetry into Clinical Practice: What It Takes to Make Dosimetry a Mandatory Part of Clinical Practice.” Journal of Nuclear Medicine 65(12): 1846–1847. DOI: 10.2967/jnumed.124.268538

Gear, J. et al. 2023. “EANM enabling guide: how to improve the accessibility of clinical dosimetry.” European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 50(7): 1861–1868. DOI: 10.1007/s00259-023-06192-5

Chicheportiche, A. et al. 2023. “Impact of Single-Time-Point Estimates of 177Lu-PRRT Absorbed Doses on Patient Management: Validation of a Trained Multiple-Linear-Regression Model in 159 Patients and 477 Therapy Cycles.” Journal of Nuclear Medicine 64(10): 1610–1616. DOI: 10.2967/jnumed.122.265196

Spink, S. et al. 2024. “Estimation of kidney doses from [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-TATE PRRT using single time point post-treatment SPECT/CT.” EJNMMI Physics 11(1): 68. DOI: 10.1186/s40658-024-00677-8

Vergnaud, L. et al. 2024. “A review of 177Lu dosimetry workflows: how to reduce the imaging workloads?” EJNMMI Physics 11(1): 65. DOI: 10.1186/s40658-024-00674-x