GastroEnteroPancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors (GEP-NETs) include tumors with well-differentiated cells arising from the gastrointestinal tract and pancreas neuroendocrine systems. These relatively indolent, slow-growing tumors might be hormonally functional or non-functional. If hormonally functional, GEP-NETs can produce high levels of peptide hormones or biogenic amines that may be associated with hormonal syndromes (e.g., insulinoma, glucagonoma, gastrinoma) or hereditary tumor syndromes such as multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) types 1, 2 and 4 as well as Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome (VHL), neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1), and tuberous sclerosis (Klöppel G. 2017; Rogoza O et al. 2022).

Classification

The current WHO classification published in 2019 identifies three main groups of GEP-NENs: well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-NETs), poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas (GEP-NECs), and mixed neuroendocrine/non-neuroendocrine neoplasms (MiNENs) (Rosa et Uccella 2021). The basis for their classification includes cellular morphology (histological differentiation) and proliferative grade features (mitotic count and Ki-67-related proliferation index). Based on this classification, GEP-NETs are graded into three groups: NET G1, NET G2, and NET G3 (Table 1).

|

Terminology |

Differentiation |

Grade |

Mitotic ratea |

Ki-67 indexb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

NET, G1 |

Well-differentiated |

Low |

<2 |

<3% |

|

NET, G2 |

Intermediate |

2-20 |

3-20% |

|

|

NET, G3 |

High |

>20 |

<20% |

|

|

SCNEC |

Poorly differentiated |

High |

>20 |

>20% |

|

LCNEC |

>20 |

>20% |

||

|

MiNEN |

Well or poorly differentiated |

Variable |

Variable |

Variable |

Table 1: Classification and grading for NENs of the gastrointestinal tract

AMitotic rate, the number of mitosis/2 mm2. BKi-67 index, counting ≥500 cells in the regions of highest labeling (hot-spots) which are identified at scanning magnification. NENs, neuroendocrine neoplasms; NET, neuroendocrine tumor; NEC, neuroendocrine carcinoma; SCNEX, small neuroendocrine carcinoma; LCNEC, large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma; MiNEN, mixed neuroendocrine non-neuroendocrine neoplasm.

Epidemiology

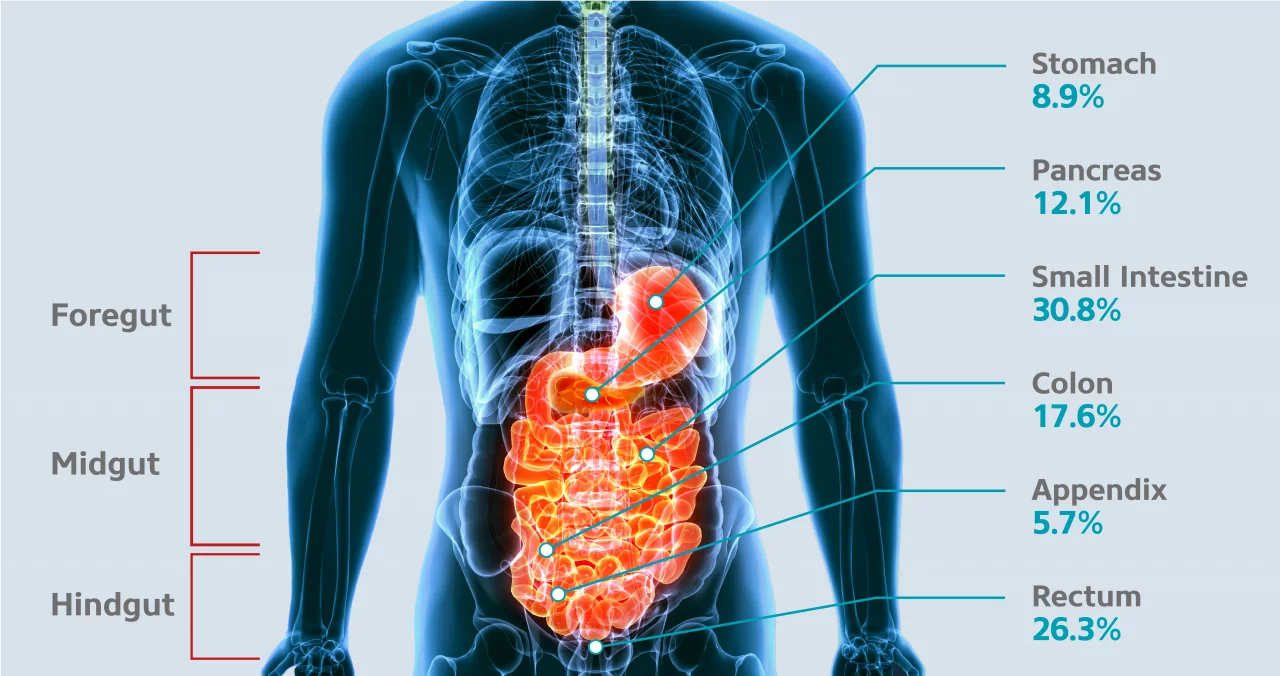

GEP-NETs are a rare disease characterized by a relatively indolent growth rate. Retrospective epidemiological data from national and regional registries suggest a GEP-NET incidence of 1.33 - 2.33 in Europe and 3.56 in the US per 100,000 population (Pavel M et al. 2020). The incidence of GEP-NETs seems to be increasing, probably due to improved imaging trends and awareness about histology (Cives M et Strosberg JR 2018). The most common primary GEP-NET sites are the small intestine (30.8%), rectum (26.3%), colon (17.6%), pancreas (12.1%), stomach (8.9%) and appendix (5.7%) (Frilling et al. 2012) (Figure 1).

Clinical manifestation

Most GEP-NETs are non-functioning, so their diagnosis is often delayed for many years. Most patients are diagnosed incidentally or present with non-specific symptoms such as bloating, weight loss, or abdominal pain related to tumor mass effects or metastases (Rogoza O et al., 2022). In turn, patients with functional GEP-NETs present distinct clinical syndromes resulting in the secretion of high amounts of bioactive compounds such as hormones or peptides. As a result of excessive secretion of substances such as serotonin, histamine, tachykinins or prostaglandins, symptoms such as flushing, diarrhea or bronchoconstriction can occur (Rogoza O et al. 2022).

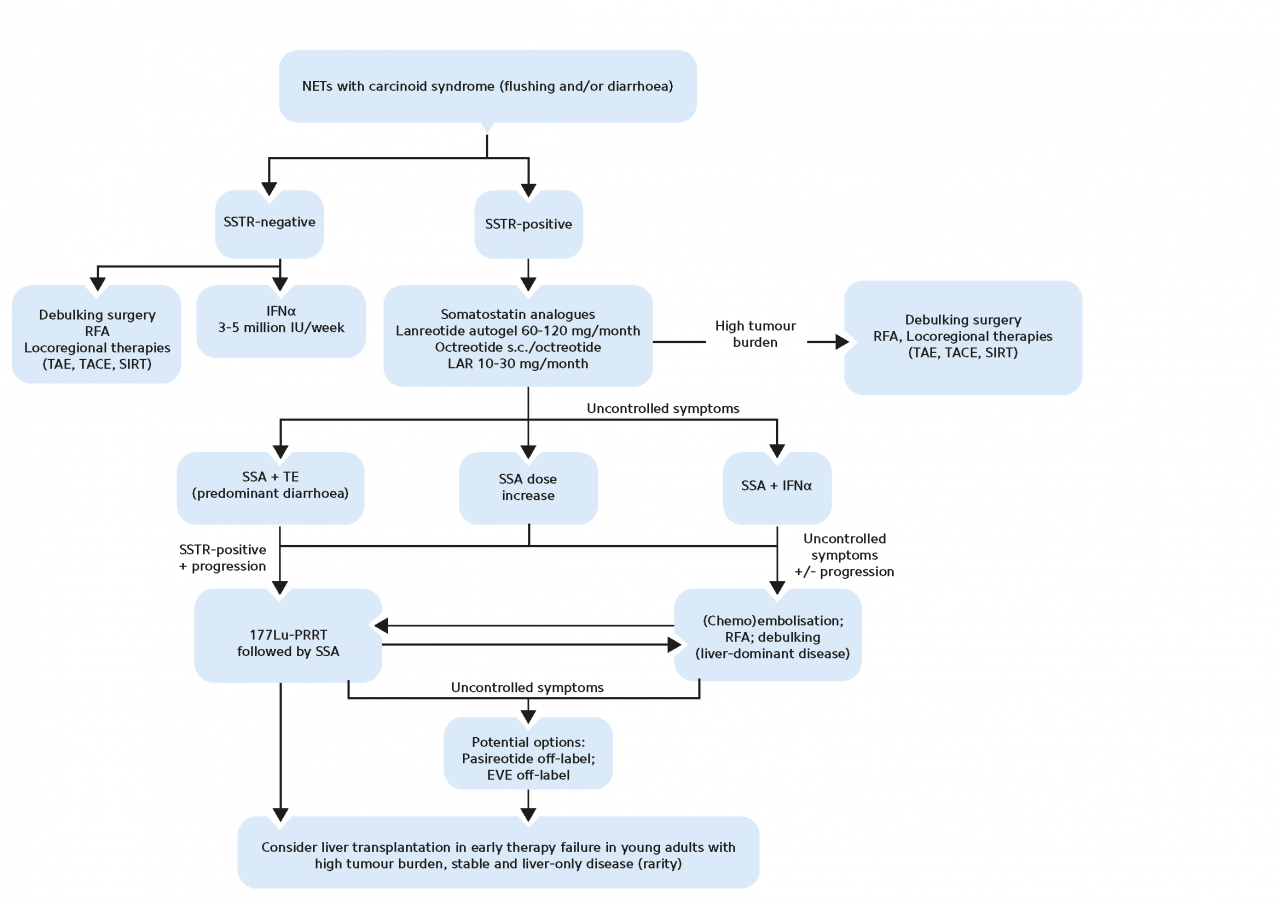

A common hormonal complication accompanying functioning GEP-NETs is carcinoid syndrome (CS) and is defined by chronic diarrhea and/or flushing in the presence of systemic elevated levels of serotonin or its metabolite 5-hydroxyindolacetic acid (5-HIAA) (Grozinsky-Glasberg S et al. 2022).

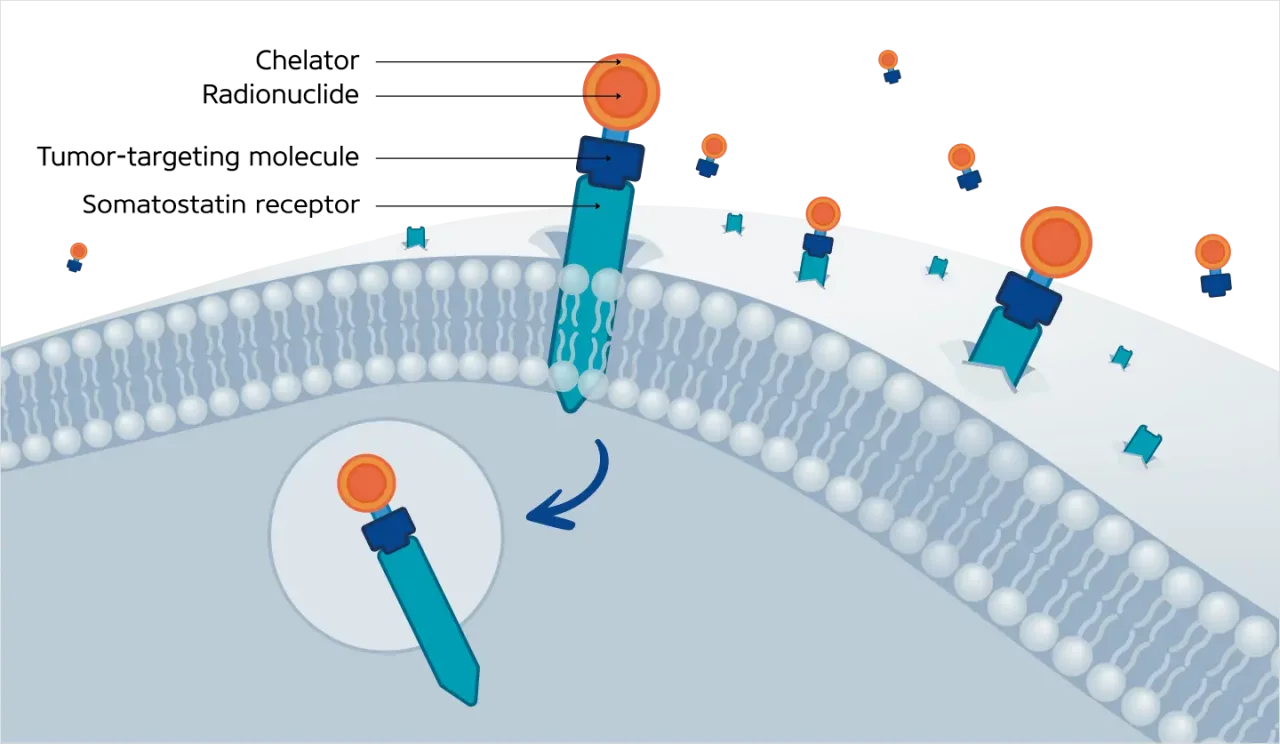

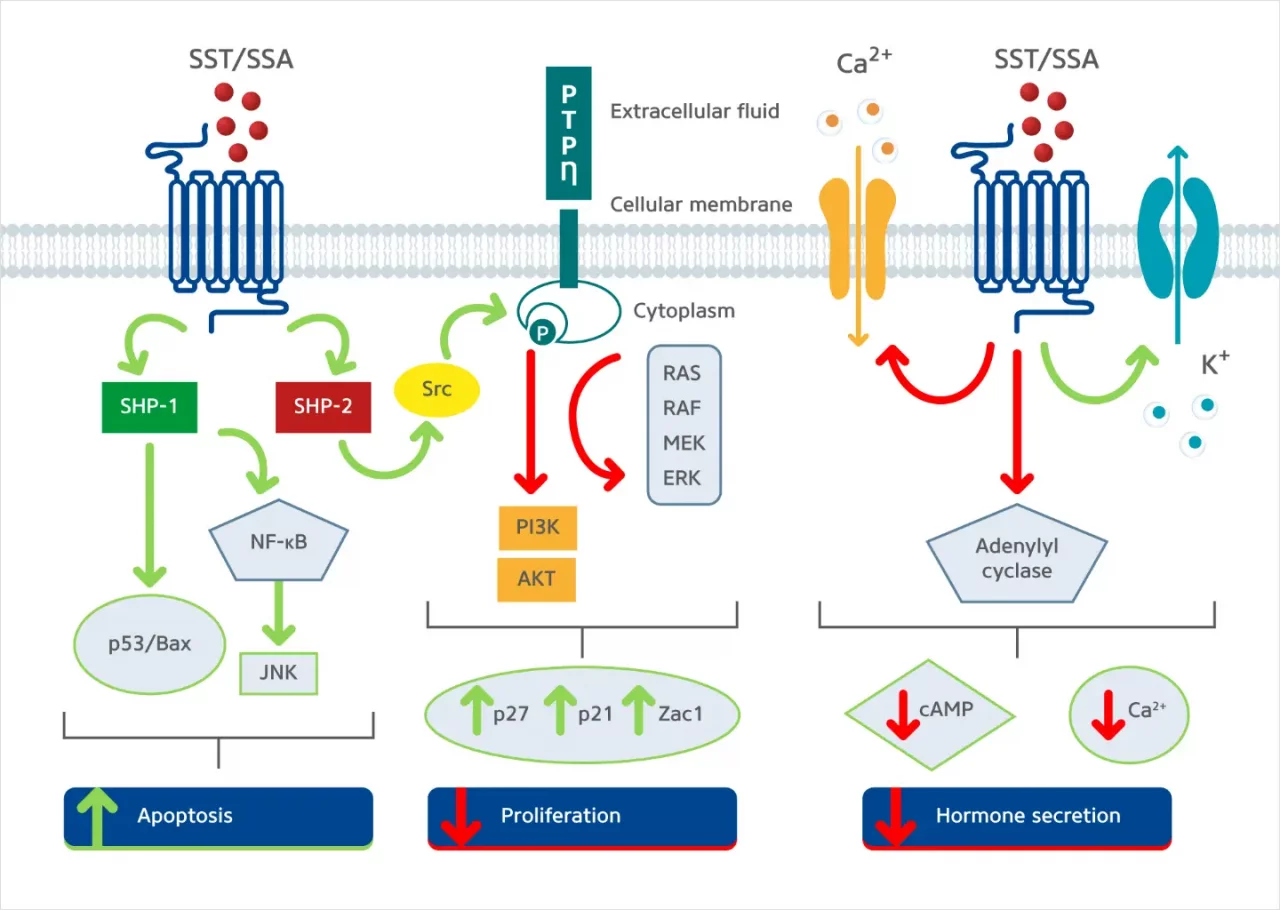

Somatostatin signaling

Somatostatin is a naturally occurring peptide hormone primarily secreted by the pancreas, gastrointestinal tract, and central nervous system. Somatostatin is involved in inhibiting five somatostatin receptors (SSTR1 to SSTR5), all G-coupled protein receptors (GCPRs), which play roles in numerous metabolic processes related to neurotransmitters and endocrine and exocrine secretions (Eychenne R et al. 2020). Most GEP-NETs, around 80%, overexpress somatostatin receptors (SSTRs) on their cell membrane, namely SSTR types 1 and 2. This makes targeting the SSTR a valuable tool for diagnosing, staging, and treating GEP-NET patients (Baldelli R et al. 2014). Targeting SSTR signalling in GEP-NETs at a functional level inhibits hormonal secretion, cell cycle progression, angiogenesis, and cell migration (Eychenne R et al., 2020) (Figure 2).

SSTR-Targeted Imaging

As most GEP-NETs overexpress somatostatin receptors (SSTR) on their tumor surface, functional imaging using radiolabeled diagnostic agents that specifically detect SSTR, predominantly SSTR2, exhibit greater sensitivity than conventional imaging techniques (Ito et Jensen 2017).

Radiopharmaceuticals currently used for functional imaging of GEP-NETs in routine clinical practice include 111In-DPTA-peptides detected with SPECT/CT-imaging or 68Ga-DOTA-peptides detected with PET alone or combined with CT-imaging (PET/CT) (Eychenne R et al. 2020).

You can learn more about SSTR-targeted imaging in the Theranostics section.

SSTR-Targeted Treatment

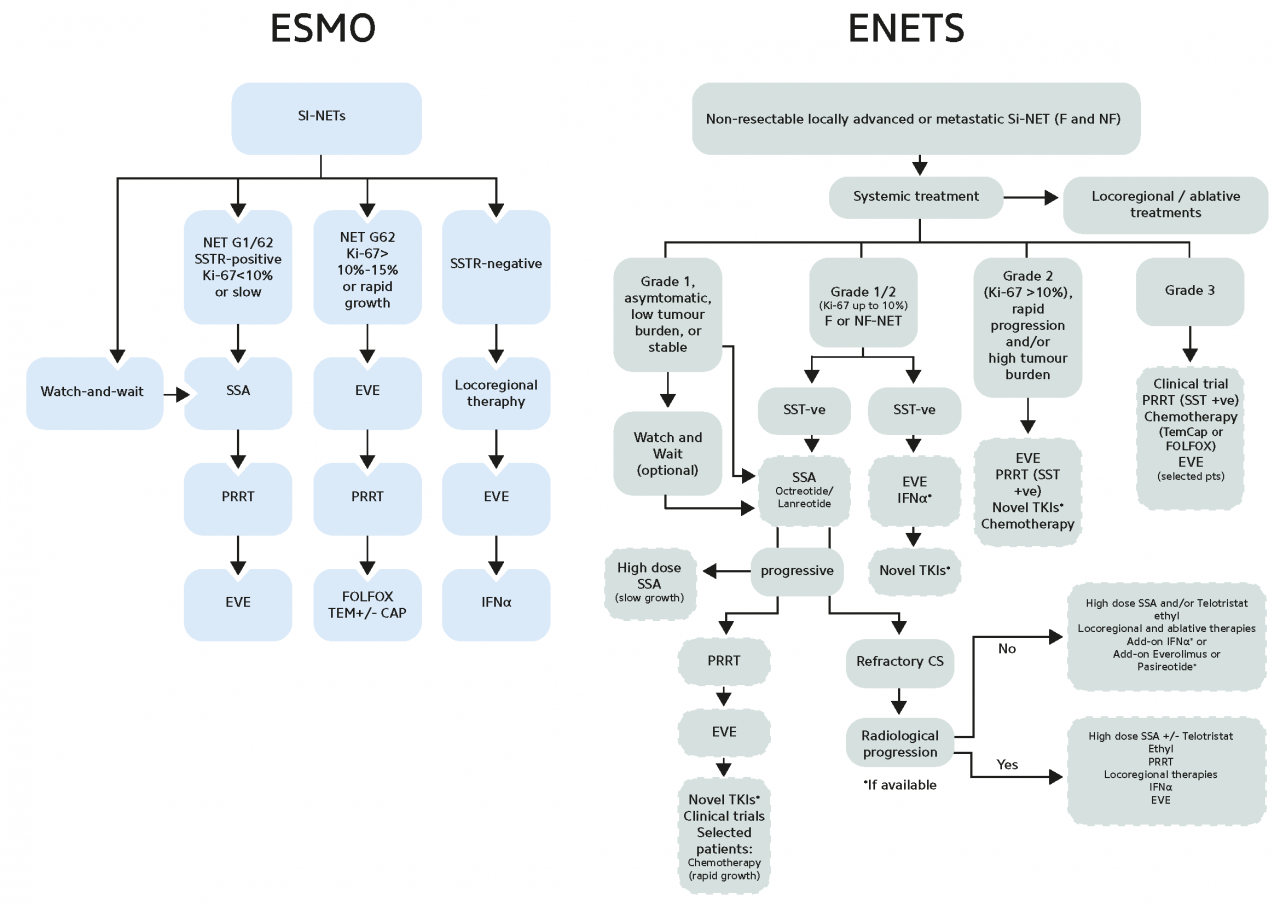

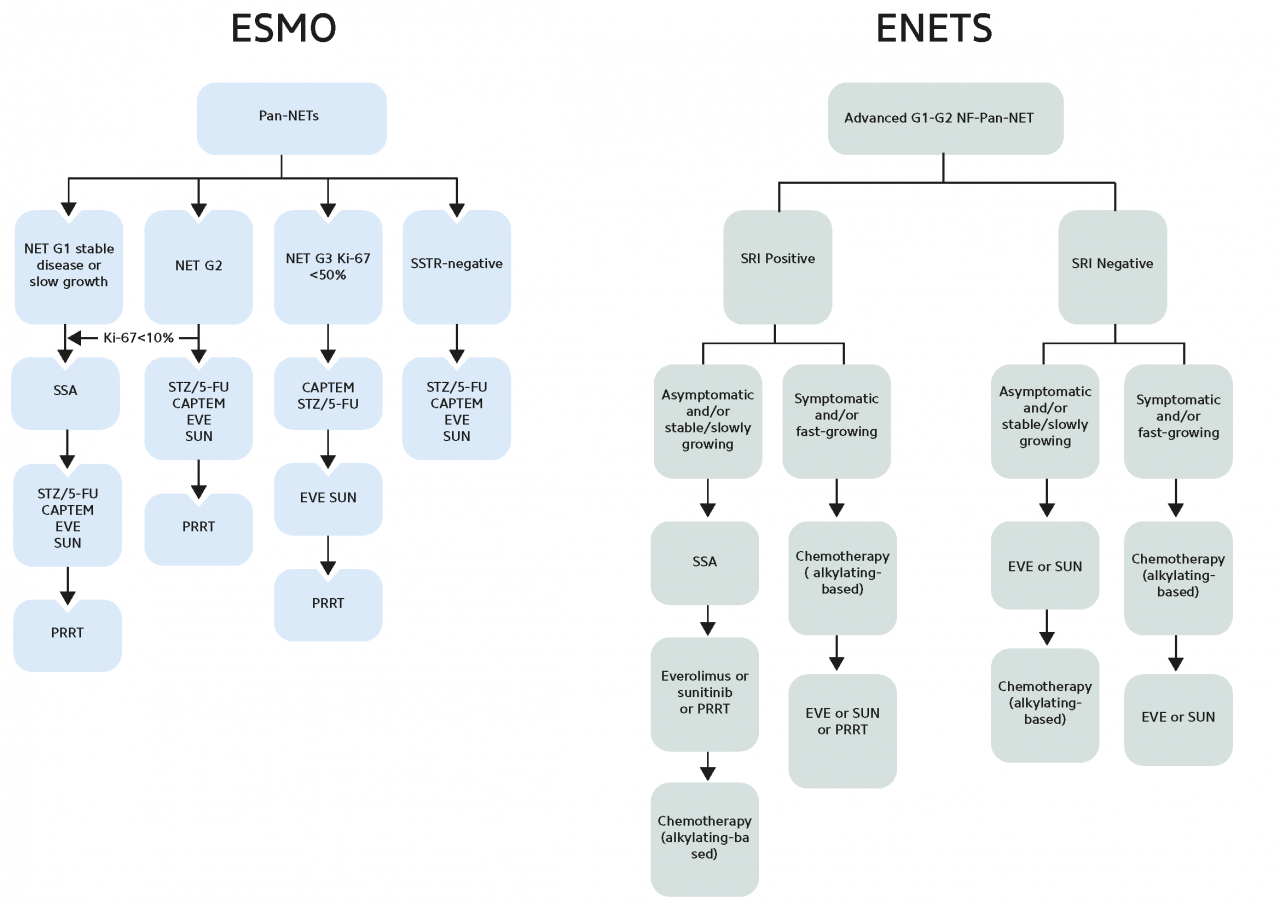

SoSomatostatin analogs (SSA) are used as standard first-line therapy in functioning NETs for symptom control, and they are also an established anti-proliferative therapy for metastatic GEP-NETs. Most frequently, they are used in first-line treatment due to their modest activity and the setting in which they have been studied (i.e., placebo-controlled trials). SSAs are very well tolerated but have shown low response rates (Pavel M et al. 2020).

In patients with progressive disease, the overexpression of SSTRs on the tumor surface of GEP-NETs can also be exploited for treatment using therapeutic radiopharmaceuticals. For therapeutic purposes, specific peptides can be labeled with the β-emitters yttrium-90 or lutetium-177. Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy, tolerability, and manageability of PRRT with radiolabeled somatostatin analogs, leading to their inclusion in clinical practice guidelines for inoperable or metastasized, well-differentiated GEP-NETs (Pavel M et al. 2020; Sgouros G et al. 2020).

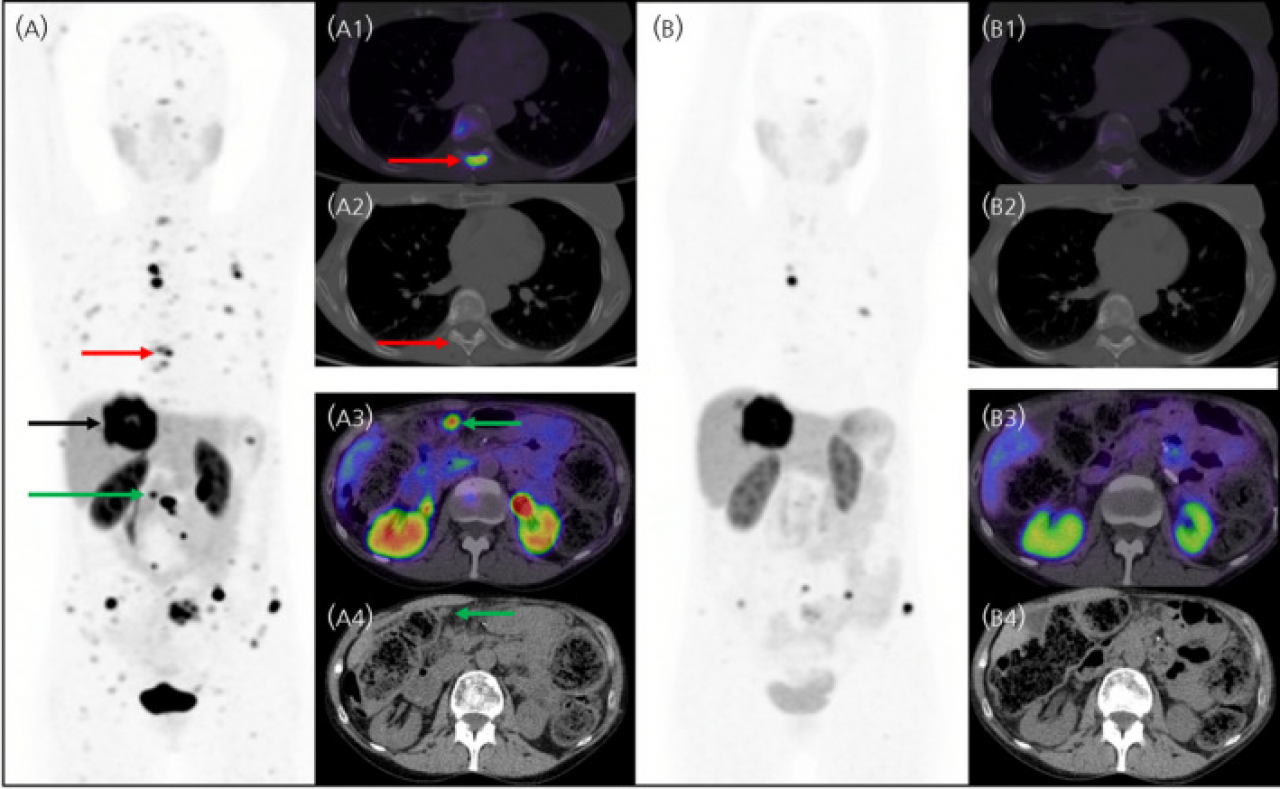

Radiopharmaceutical therapy (RPT) is a form of systemic therapy administered by intravenous injection that allows targeted delivery of radiation to tumor cells expressing high levels of SSTRs. The antitumor activity of 177Lu-based RPT relies on the ability of radiopharmaceuticals to bind to SSTRs expressed on the cell membrane of GEP-NETs, which, in the case of agonists, results in their internalization and subsequent delivery of the radioactivity directly into the intracellular space of the tumor cell (Figure 3). The retention of intracellular ionizing radiation is associated with DNA damage as well as with apoptosis due to the inability of the cell to correct the damage (Hirmas N et al. 2018).